Why Do Urban Legends Occur and Continue to Be Passed Along

What makes an urban legend?

Chilling and often disturbing 'real life' stories are still widely shared, says David Robson. Why do these tales continue to endure?

Y

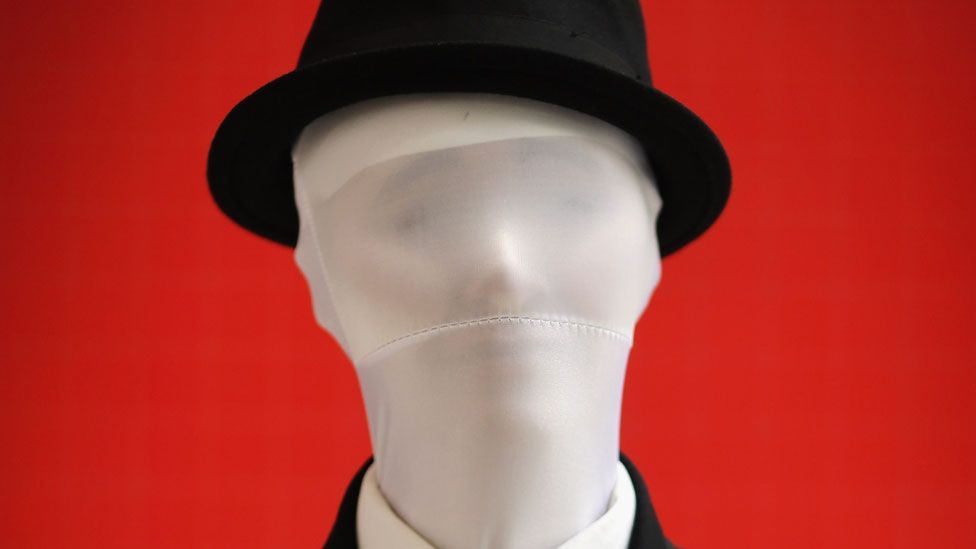

You may have already met Slender Man – the preternaturally tall, spectral being wearing a black suit and tie, with a white and featureless face. He is often seen in the shadows of photos, stalking small children, and some say that he can drive you insane with terror. One of his first sightings came at an asylum; after a bloody rampage in the hospital, a photo emerged of his ghostly but silent presence hiding in the stair well while the chaos erupted around him.

Rising from humble internet forums, this modern urban legend has now inspired a slew of fan fiction, best-selling computer games and a series of short movies. But the tale has also taken a darker turn as the line between myth and reality became blurred: some are convinced that they have spotted Slender Man lurking behind trees and scaling the sides of buildings; and in January there were more claimed sightings in the UK reported by the British tabloids.

"I find it fascinating, because it really shows how folklore is always adapting to new technologies and media, rather than being some kind of relic of the past," says anthropologist Jamie Tehrani at the University of Durham.

The question is, why did this particular story infect people's minds in a profound way? Assuming such widely-shared tales are not actually true, what makes them endure? During the last decade psychologists have started to sift out some of the features that make certain stories contagious, potentially explaining the appeal of everything from urban legends to Little Red Riding Hood.

To understand the appeal of tales like Slender Man, it makes sense to begin with his first outing. Starting on the Something Awful forum in 2006, a user, "Victor Surge", posted two photos, doctored with the ghostly figure in the background. Beneath, he wrote some short, enigmatic captions, implicating the shadowy figure in the mysterious abduction of 14 children.

One of two recovered photographs from the Stirling City Library blaze. Notable for being taken the day which 14 children vanished and for what is referred to as "The Slender Man". Deformities cited as film defects by officials. Fire at library occurred one week later. Actual photograph confiscated as evidence. — 1986, photographer: Mary Thomas, missing since June 13th, 1986.

And:

We didn't want to go, we didn't want to kill them, but its persistent silence and outstretched arms horrified and comforted us at the same time… — 1983, photographer unknown, presumed dead

His descriptions are chilling, for sure – but perhaps part of the appeal lay in the gaps of Surge's story, which leave space for us to project our own imagination. "Victor Surge's original post provides tantalising hints of a larger narrative involving a terrifying creature," notes semiotician Jeffrey Tolbert. "It suggests the being's unique power to induce violence, and indicates that the photographers responsible for the images are missing or dead – and thus sets the stage for the processes that would lead to the communal construction of an entire narrative tradition." Just take a look at the following video to see the lengths that some would go to in order to build that mythology:

Contains elements of horror; content may disturb some viewers

This video is no longer available

It's probably no coincidence that, within that skeletal framework, Slender Man also evokes some familiar fairy tale elements; psychologists are finding that there is good reason that those stories often follow certain set formulae.

Firstly, tales of the supernatural may be especially appealing since they are "minimally counter-intuitive", combining both the familiar and the bizarre. "They depart from what's expected and as a result push us to process the information more deeply," says Ara Norenzayan at the University of British Columbia, "so we remember more and are more likely to retell them." Counter-intuitive elements could include a talking animal, or a pumpkin that turns into a chariot – but it's not so much the nature, as the number of these narrative devices that seems to be crucial. Norenzayan's analysis of Grimm's fairy tales found that the most popular stories – as measured by the number of times they have been cited online – only have two or three supernatural surprises. Our brains, it seems, have only so much room for the bizarre before it becomes too confusing to be enjoyable.

Consider Little Red Riding Hood. "There are only a couple of things that don't make sense – such as the talking wolf and her and the grandmother being rescued from the stomach," says Tehrani. "But the idea of a girl visiting her grandmother – that makes perfect sense." Yet the lesser-known tales such as The Donkey Lettuce flout those constraints. "Honestly, if you wanted me to summarise it, I couldn't – there's just so much weird stuff going on." The same goes for contemporary urban legends. Tehrani recently examined the evolution of the Bloody Mary myth – that if you chant an incantation into the mirror, a mutilated face will appear before you. There are many different variants involving different characters and events, but, as with Grimm's tales, the most popular almost always contained just two or three unsettling events.

Crucially, Slender Man seems to titillate the brain's sense of surprise in exactly the same way. "Slender Man is minimally counter-intuitive because, on the one hand, we can attribute psychological motivations to him just as we would any other person," says Tehrani. "But on the other, he appears to be able to violate the laws of physics, by appearing out of thin air, and the laws of biology – he can stretch and shrink his body and grow tentacles." In other words, the tale offers just enough hints of the eerie to pique our curiosity, without leaving us feeling too alienated.

Delighting in disgust

In terms of their wider themes, psychologists have found that, perhaps unsurprisingly, the most popular tales also tend to evoke strong emotions – and the feeling of disgust seems to make a story particularly potent. Julie Coultas at the University of Sussex recently asked subjects to read and share different versions of common urban legends, some more disgusting than others. One, in particular, seemed to stay in her students' mind, about a woman who takes her poodle to Vietnam. As the woman fumbles with her order for a delicious steak, the dog trots into the kitchen. It is only when the bill comes, minus the cost of the meat, that she realises she has eaten her beloved pet. Even a year later, the students were still struck by the tale, she says. "It was amazing to see the difference in recall between the high and low disgust content stories," says Coultas. Perhaps that can explain why urban legends are so often in very bad taste.

We are also drawn to themes of survival – which is why many stories deal with life and death. That makes sense, given our evolution – stories would have been an important way of transmitting valuable information that could save our skin at a later point.

But the most memorable tales, according to Tehrani's recent lab experiments, involve some kind of social connection; we just can't forget a piece of lurid gossip. His participants were given a choice of tales and asked to choose one to read, remember and pass on to another person. Each tale reflected the above biases in a different way, and it seemed to have a big effect on their popularity. One told the story of a woman who died after a poisonous spider made a nest in her unwashed beehive haircut. Dealing with death, it was a classic survival tale – but although it piqued people's interest, it proved to be less easily remembered than some of the others. In contrast, a more memorable story concerned a woman who had cybersex with an unknown man, only to find out months later that it was her father. It's hardly Jane Austen, but the story requires you to consider others' motives and decisions, tapping into our social bias. (Others, along a similar vein, might include the story of the inadvertent biscuit thief that ends in excruciating embarrassment.)

Slender Man fans like to dress up as the feared character (Getty Images)

Appealing to both the social and survival biases, the story of a serial killer who lures women to their death, with the sounds of a baby crying proved to be most popular of all. Tehrani thinks this too can be explained by considering human prehistory; as we lived in bigger societies, our survival depended less on environmental dangers and more on other people, so we are primed to take notice of quirks in other people's behaviour, as much as more immediate dangers.

Surprisingly, Slender Man only partially confirms these findings. "There are elements of these memes that exploit our survival bias, such as the fact he targets vulnerable children in a typical woodland setting, and our emotion bias – fear and disgust," Tehrani says. Yet the story is almost completely lacking in social information. Even something as simple Little Red Riding Hood, he says, asks us to exercise our ability to understand that the wolf is lying as he builds up the girl's trust. "Slender Man," in comparison, "simply entices his victims using some kind of paranormal power"; there is no social conundrum for us to crack.

One possibility is that Slender Man is just a fluke – the exception that proved the rule. More intriguing, however, is the idea that it instead reflects a deeper change in the way that we craft folk tales thanks to the internet. Tehrani points out, for instance, that social stories may be more memorable but they weren't necessarily more enjoyable, according to his participants. Memorability would have been crucial when stories were passed mouth to ear, but with the cut and paste buttons on our desktop, it perhaps plays less of a role. "We may find social content easier to remember, but actually, we are just as likely to want to hear about stories relevant to survival and to pass them on – so the advantage of social information over other biases disappears," Tehrani says.

Slender Man is often barely visible in doctored photographs (Bob Mical/Flickr/CC BY 2.0)

In other words, as more stories are shared on the internet, our stories may lose some of their social nuances, and become even more ghoulish. "It is certainly feasible that story-telling in the digital age may evolve in a very different way from the fairy tales of the past, which were shaped by the cognitive constraints of oral transmission," says Tehrani.

These are just musings, of course; Tehrani has yet to study the appeal of Slender Man formally, though he plans to look into the stories on creepypasta.com – a website that allows users to share and contribute many of these modern urban myths. "It's very much on our to-do list."

Story-telling is, after all, a craft like any other, evolving with tools and technology. Our entertainment has already seen monumental changes in literature and cinema. But perhaps those transformations are trickling down to the myths and legends we tell each other too – the humble stories that form a substantial, though neglected, contribution to our culture. It is an intriguing thought that the elements forged by storytellers from across the millennia are now being cast into a very different folk tale – the beginning of a tradition that our descendants may be reading and sharing on their tablets in centuries to come.

Share this story on Facebook , Google+ or Twitter .

Source: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20150126-how-to-create-an-urban-legend

0 Response to "Why Do Urban Legends Occur and Continue to Be Passed Along"

Post a Comment